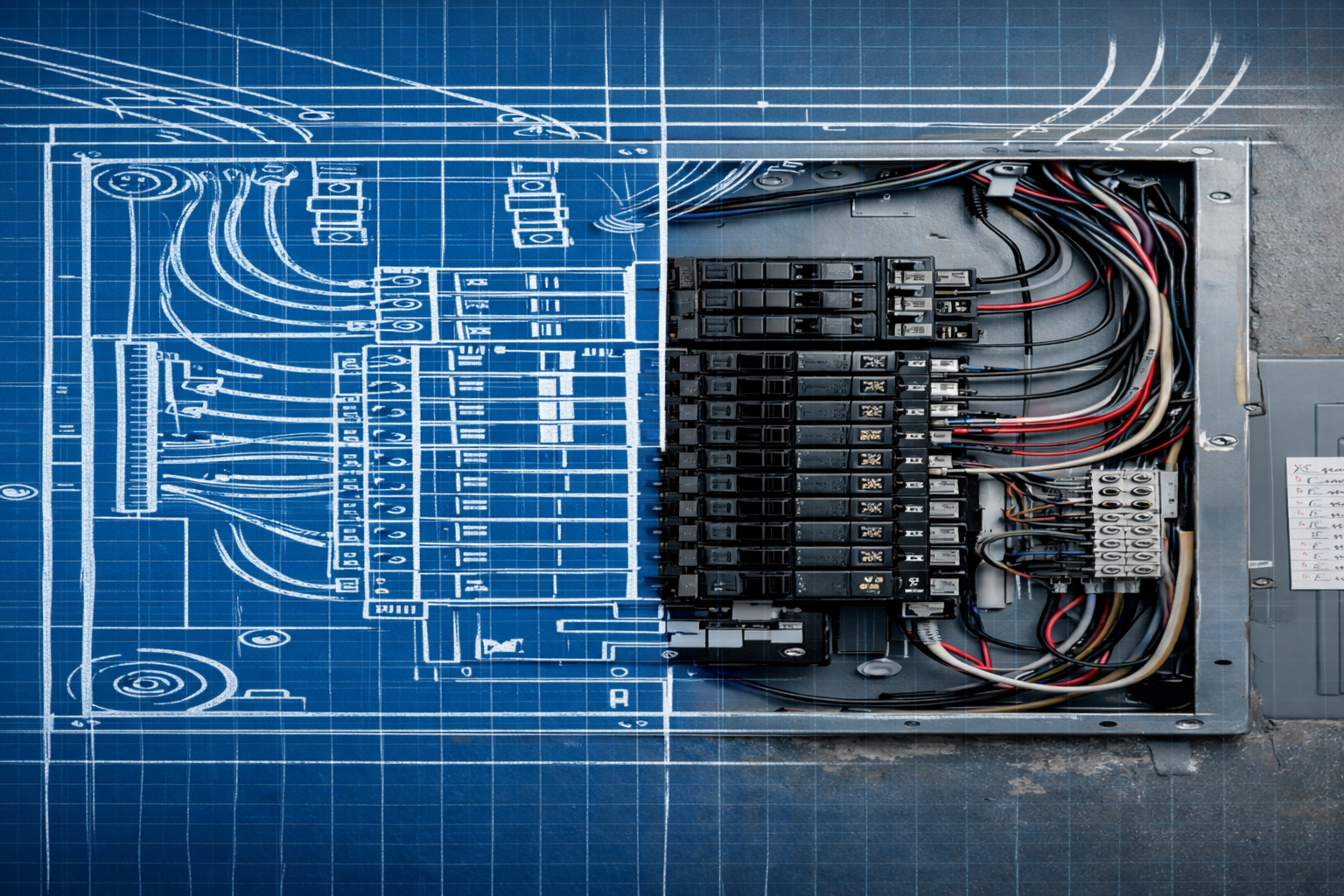

How excess metal, oversized ratings, and misplaced safety factors are quietly increasing failures—and how global engineering leaders design smarter instead.

In electrical engineering, one belief has gone largely unquestioned for decades:

“If it’s bigger, thicker, and higher-rated, it must be safer.”

Yet some of the most costly electrical failures in modern infrastructure—from data centers to manufacturing plants—have occurred in systems that were heavily over-engineered on paper.

The problem isn’t poor intent.

It’s misallocated engineering effort.

This article explores how electrical infrastructure is often over-designed where it adds no safety, under-designed where it matters most, and how leading global players approach design differently.

The Hidden Cost of “Designing for Everything”

Over-design is rarely accidental. It usually stems from:

According to IEEE failure analysis studies, a significant percentage of electrical system failures are caused by thermal stress, poor layout, and maintenance constraints—not insufficient ratings.

Yet many designs still focus on:

…while ignoring real-world operating conditions.

Where Over-Engineering Adds Little or No Safety

1. Thick Enclosures Without Thermal Strategy

It’s common to specify 2.5–3 mm thick panels for indoor installations with minimal environmental exposure.

Real-world issue:

Thicker metal increases thermal inertia, trapping heat longer during peak loads.

Real Example

In multiple Tier-2 data centers across Asia, post-failure audits revealed:

This led to premature relay failures and nuisance tripping, despite “robust” construction.

Companies like Schneider Electric and Rittal emphasize thermal simulations over material thickness for this exact reason.

2. Oversized Conductors That Never Reach Design Load

Designers often oversize cables by two or three levels “for safety”.

What actually happens:

Industry Insight

ABB has published multiple technical notes highlighting that cable overheating is more often caused by poor grouping and routing, not undersized cross-sections.

Oversizing without layout redesign creates the very heat problems it aims to prevent.

3. High IP Ratings in Controlled Indoor Environments

Specifying IP65 or IP66 enclosures inside clean, air-conditioned facilities has become routine.

Why this backfires:

Real Example

A pharmaceutical manufacturing facility in India faced repeated HMI failures inside IP65 panels installed indoors.

Root cause: condensation cycling due to temperature differences, not dust or water ingress.

Global manufacturers like Siemens now recommend application-specific IP selection, not maximum IP by default.

Where Under-Engineering Causes Real Failures

While some areas get excessive attention, others are dangerously ignored.

1. Thermal Design and Heat Dissipation

Across industries, thermal neglect is the leading silent killer of electrical systems.

Common misses:

Real Example

A well-known automotive OEM supplier experienced repeated PLC shutdowns. Investigation showed:

The hardware was “high-rated”—but thermally blind.

2. Poor Internal Layout and Segregation

Even premium components fail when layout is compromised.

Typical issues:

Industry Reference

Rockwell Automation explicitly states that panel layout discipline impacts reliability more than component brand.

Yet layout is often rushed or treated as cosmetic.

3. No Design for Maintainability

Maintenance is rarely a design priority.

Results:

Real Example

Post-incident reports from oil & gas installations frequently cite:

Failures weren’t due to component ratings—but human interaction constraints.

The Misuse of Safety Factors

Safety factors are essential—but dangerous when misused.

Common Mistakes

A 1.5× margin on everything doesn’t make a system safer—it makes it unpredictable.

How Global Leaders Design Differently

Top engineering-driven organizations don’t eliminate safety margins—they place them intentionally.

What Companies Like ABB, Siemens & Schneider Do Differently:

Their focus is risk-based engineering, not material-heavy engineering.

Smarter Allocation of Cost and Redundancy

True safety comes from targeted investment, not uniform excess.

Smart Design Focus Areas:

Comparison Table: Wrong vs Right Engineering Focus

|

Aspect |

Over-Designed Approach |

Smart Engineering Approach |

|

Enclosure |

Thicker metal |

Thermal-optimized design |

|

Cabling |

Excessively oversized |

Load & routing optimized |

|

IP Rating |

Maximum everywhere |

Application-specific |

|

Safety Factor |

Blanket margins |

Risk-based margins |

|

Reliability |

Assumed |

Measured & validated |

The Real Engineering Question

The question is no longer:

“How much can we over-design?”

It is:

“Where does design effort actually reduce failure risk?”

Because in electrical infrastructure, misplaced safety is just hidden risk.

Conclusion

Electrical infrastructure doesn’t fail because it wasn’t “strong enough”.

It fails because it wasn’t thought through deeply enough.

Over-engineering the wrong areas creates:

While under-engineering critical areas quietly sets the stage for failure.

The future of reliable electrical systems lies in intentional, evidence-based engineering—not excess.

FAQs

1. Is over-engineering always bad?

No. Over-engineering is harmful only when it’s misapplied. Targeted redundancy improves safety; blind excess does not.

2. What causes most electrical panel failures?

Thermal stress, poor layout, and maintenance constraints—not low component ratings.

3. Are higher IP ratings safer?

Only when the environment demands it. Otherwise, they can increase heat and condensation risk.

4. Do bigger cables always improve reliability?

No. Poor routing and congestion often negate the benefits of oversized conductors.

5. What’s the most ignored factor in panel design?

Thermal management and future load expansion.